The Phyloreferencing project team had their third face to face project meeting from Mar 21-23, 2018, at the UF campus in Gainesville. A day longer than previous ones, this meeting was more extensive, but we felt the extra day was necessary to accomplish our meeting goals. We had a rather long list of items on the agenda, and it was quite a miracle that we covered nearly all of them. This report summarizes four major topics of the meeting: (1) ontology of phyloreferences, (2) phyloreference curation tool, (3) use case development, and (4) specifier matching. In addition, this blog also documents our discussions of some important concepts and unresolved challlenges. Overall, this meeting set a clear direction for the way ahead, laid out goals, and planned tasks for the next six months.

Ontology of Phyloreferences

We will prioritize our time until at least August to transcribe the content of Phylonyms: a Companion to the PhyloCode, essentially a list of clade definitions to be published as a book in the near future, into an ontology of phyloreferences. The idea is to officially release the ontology and publish an accompanying journal paper closely coinciding with the publication of the Phylonyms volume. Our plan for the paper would be to describe the ontology itself, how it works, and examples, such as queries, that illustrate how the ontology is useful for research. This paper would not focus on the theory of phyloreferencing and its relevance in the broad biology research context, but it would include a brief description of phyloreferencing, and a description of the specification as the basis for why the phyloreferences in the ontology were constructed in the way they were.

So we can start coordinating and planning everyone’s work to complete in time, we first need to get an idea of the time required for curating a clade definition, converting it to a phyloreference (in OWL format), and validating the phyloreference against the reference phylogeny based on which the clade definition is made. Then we will be able to assess what target date is realistically achievable for completing the first release of the ontology.

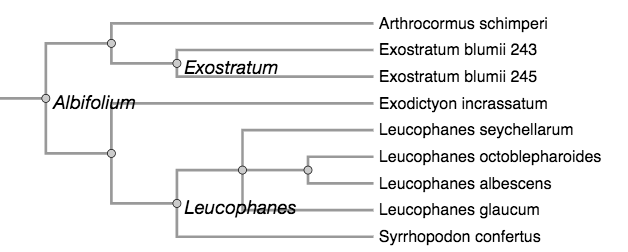

For demonstrating the utility of this ontology of phyloreferences, our aim would be to show that it affords capabilities not offered by the clade definition records in the Phyloregnum database alone. We determined two preliminary use cases that should be meaningful, and realistically implementable. The first is to use reasoning to infer relationships between phyloreferences on the original (reference) phylogeny. Specifically, we would ask “Can a machine infer relationships between clade definitions applied to the same given phylogeny?” For example, on the phylogeny in the figure below (redrawn from Fisher et al., 2006), the machine should tell us that Exostratum and Leucophanes do not share descendants, and that Albifolium includes Exostratum and Leucophanes because all the descendants of Exostratum and Leucophanes are also descendants of Albifolium. The same question can also be investigated on a different phylogeny. By comparing results between the original phylogeny and another one (for example, a large synthetic phylogeny such as the Open Tree of Life), we would be able to ask whether the relationships between the clades can be recovered.

This leads to the second use case for illustrating the utility of the Ontology of Phyloreferences, namely applying the phyloreferences in the ontology to the Open Tree of Life as a comprehensive base phylogeny, and then asking some questions about the ontology as a whole. For example, in line with question just described, we can ask how many clade definitions maintain their original relationships when applied to the OToL? We can also ask how many clade definitions are not supported as a clade on the OToL (these will necessarily be stem-based definitions, and use at least three specifiers); how many definitions resolve to a labeled node versus nodes without a label (name), and for labeled nodes, is the label the same or similar to the label for the clade definition (all clade definitions in the Phylonym volume will be named); and of the resolving clades, how many are congruent in content with the content they had in the original reference phylogeny. These kinds of data science questions can really only be answered once clade definitions have computable semantics, and this will illustrate how the ontology, and by extension phyloreferencing as a method, has utility considerably beyond a simple database of definitions.

We will no doubt encounter major challenges in the endeavor of curating this ontology. For example, to start with a large percentage of the phylogenies will likely not be readily available in a machine-readable format (e.g., a Newick/Nexus file). Once obtained in machine readable format, some may not even contain all the specifiers used in a definition. Those problems will need to be addressed, but part of the point of the endeavor is to start surfacing and documenting what the issues are.

Phyloreference curation tool

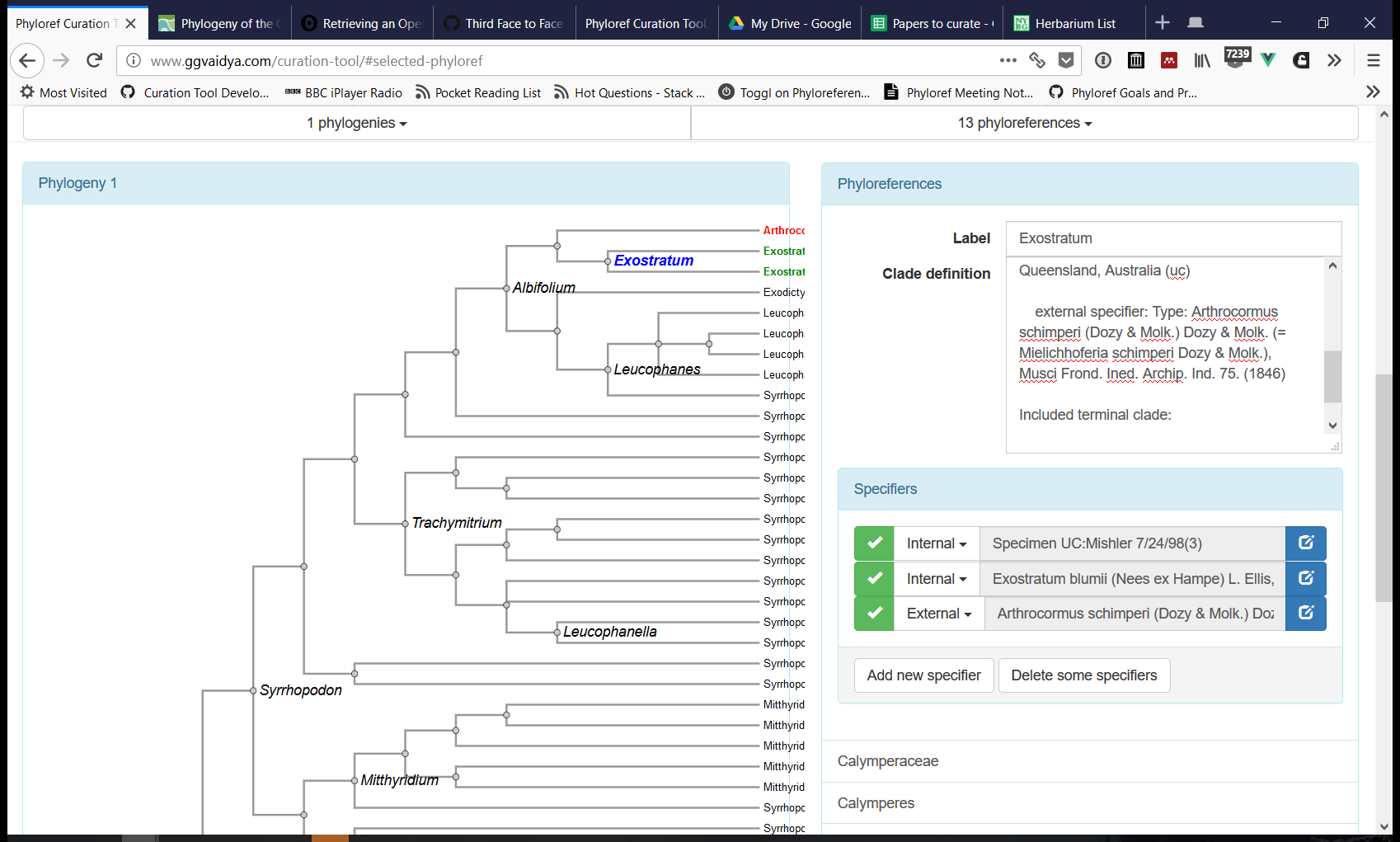

The Curation Tool (see a prototype here) has been the primary target of software development in the last few months. This tool produces files in the Phyloreference Exchange (PHYX) format, which is JSON-LD that describes phyloreferences and includes annotated phylogenies against which they can be tested. Phyloreferences in PHYX format can then be converted to OWL for validating that they resolve, on the original reference phylogeny, to exactly the same clade intended by the author (a step we call testing). Next we will add software support for concatenating PHYX files into a shareable Ontology of Phyloreferences.

Immediately though our software development goal is to provide project members with an interface they can use to curate phyloreferences into PHYX files. We walked through the latest development version of the Curation Tool, and identified various software development tasks, grouped on Github into projects as follows:

-

Curation Tool v0.1: the minimum viable product for the Curation Tool, capable of creating, visualizing, editing and exporting PHYX files. We determined that this is largely complete, except for one feature – support for renaming nodes on a phylogeny – and additional testing to ensure that this tool is usable. We plan to reach this goal within the next few weeks.

-

Estimate rate of phyloreference curation: As soon as Curation Tool v0.1 is complete, we use it to curate phyloreferences from Phyloregnum so we can start estimating the time this takes on average.

-

Curation Tool v0.2: implement basic reasoning, for example using a Java-based server backend. Even if this is slow from the user’s perspective, it will allow PHYX files to be tested before they are incorporated into the Ontology of Phyloreferences. We plan to reach this goal in the next two months, depending obviously on the time needed for the above.

-

Curation Tool v1.0: this project collects issues that will improve the usability of the software, but are not essential to any of our goals above. We can prioritize these and schedule them accordingly for implementation after the previous goals have been achieved. Once non-developers use the Curation Tool, their feedback will help with prioritization. This is a long term goal.

Use case development

One of the ongoing challenges in organizing our software development efforts has been to pin these to driving use cases. A use case describes a research problem that requires software or infrastructure development to answer it. To directly drive and inform software development, use case descriptions must also be specific to a level that can be surprising to non-developers whose role includes creating them. Often when we colloquially refer to use cases, we actually refer more to user stories than these very specific, and as a conseqeunce well structured descriptions. To better understand the degree of structure and specificity needed, we went through an exercise to develop a mock use case for phyloreferencing.

Broadly speaking, a use case has an objective, prerequisites (typically inputs needed to accomplish the objective), pre-conditions (that have to be met or the objective can’t be accomplished), and post-conditions (the set of conditions that, if found true, indicate that the objective has been met). For our exercise we chose the following mock use case: A biologist would like to determine the relationship between a taxon according to their understanding and a clade definition on a particular phylogeny. A biologist would normally do this “by hand”, using their own expert knowledge, but here we want to describe it so that one can implement a software tool that makes the determation and shows the result to the biologist. The following breaks this down into a sufficiently specific structured use-case:

- Objective: Enable a biologist to use a computer to determine the relationship between a taxon in their understanding and a clade definition on a particular phylogeny

- Pre-requisites: (1) a phylogeny, (2) a clade definition, and (3) a set of statements that describe the biologist’s understanding of a taxon (which also need to be computationally amenable).

- Pre-conditions: (1) the clade definition should be resolvable on the phylogeny, (2) the set of statements can be matched to the phylogeny (“taxon contains X”, “taxon does not contain X”), and (3) if there is a statement that cannot be matched, then that implies that X was not sampled in this phylogeny.

- Post-conditions: (1) for each statement, we can correctly state that the statement is true, false or cannot be determined using this phylogeny, and (2) we show the results for each statement to the user.

Specifier matching, the elephant in the room?

One of the key value propositions of phyloreferences is that they are not tied to their original reference phylogeny (and in fact, do not even require one to be referenced). However, this means that for enabling matching any phyloreference to any phylogeny we are going to be faced with a massive and pervasive issue of missing specifiers. In other words, we will need a computational algorithm that for a given set of specifiers (those found on a phylogeny) which one(s) of them, if any, can substitute for a specifier used in a phyloreference but not included in the set (i.e., not included in the tree). A human expert can usually make that determination, for example through reference to appropriate taxonomic classifications. Mirroring this computationally would require a huge knowledge base of phylogenetic relationships between all kinds of specifiers. An reasonably useful approximation of this might be to use the Open Tree of Life, which would at least contain a relatively comprehensive set of tip specifiers. This will require extensive further research and evaluation.

To summarize, this was an important and productive meeting, which allowed us to develop a concrete plan for the next 6 months, align perspectives and better manage project down the road.