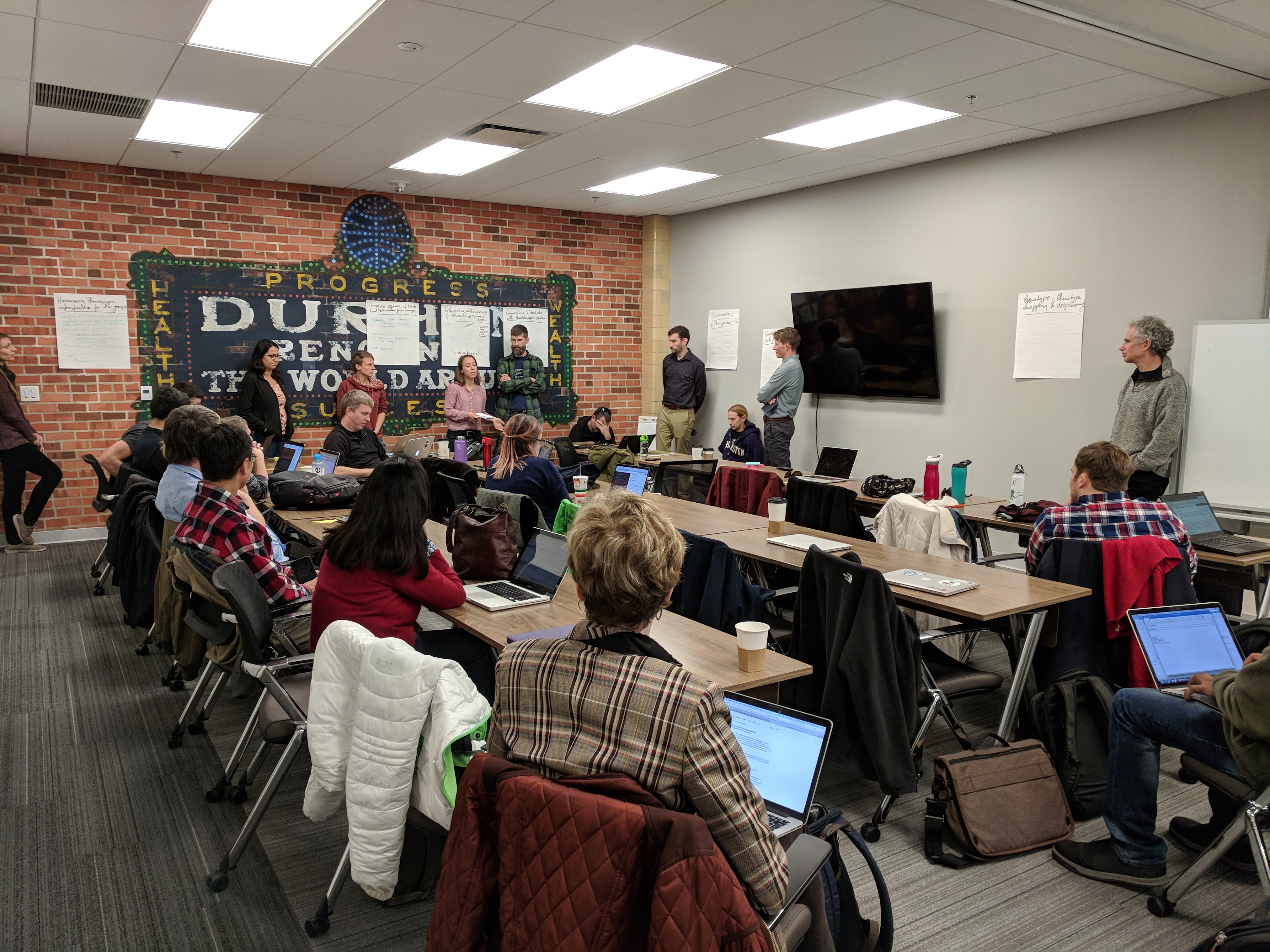

Earlier this month Gaurav and Guanyang attended the Computable Evolutionary Phenotype Knowledge workshop, sponsored by the Phenoscape project and held in Durham, North Carolina from Dec 11 to Dec 14. Phenoscape is an informatics project aiming to “create a scalable infrastructure that enables linking phenotypes across different fields of biology by the semantic similarity of their descriptions”. The workshop was in essence a hackathon, and aimed to promote data access to and interoperability with the Phenoscape Knowledgebase (KB). The goals of the hackathon were to “bring together a diverse group of people to collaboratively design and work hands-on on targets of their interest that take advantage and promote reuse of Phenoscape’s online evolutionary data resources and services”. Altogether 28 researchers participated in this hackathon. This group included both domain experts (i.e., organismal biologists or taxonomists) and programmers. In the following Guanyang and Gaurav will report their experience at this hackathon.

What we liked about the hackathon

The hackathon was a great success and also a good experience for Guanyang and Gaurav. Of the many factors that contributed to its success, we will describe just a few things that were especially impressive and inspiring. We liked the Open Space Technology approach used at the workshop. This happened at the beginning of hackathon, where participants stood up and gave a three-minute pitch to the audience about a topic that they would like to pursue as their hackathon project. The audience asked questions that will promote better understanding of the pitch, but not challenge the validity of it. More than 10 pitches were given and written down on easel pad stickers (like this), which were pasted on walls all around the meeting room. Participants then gathered around a sticker of a pitch that interested them and discussed with the pitch-maker. I (Guanyang) was interested in the PhyloPheno pitch (see details below) while Gaurav worked on the NeXML to JSON-LD conversion pitch.

The second aspect of the hackathon that was really important and enjoyable was the opportunity to interact with other researchers, both during working hours and social time. We was able to chat with most of the participants and also talked about our phyloreferencing project with several. It was interesting, and in some way, stimulating, to get different reactions about this project and more generally about taxonomy from other participants. While most lamented on the instability of names, some also remarked that taxonomic names aren’t something they want to be bothered with. The latter sentiment represents perhaps quite a good number of biologists, who may see taxonomy or nomenclature as non-science (See Dubois 2005, p. 367). Besides getting different viewpoints of taxonomy, we had exposure to some neat techniques during the workshop, such as making reproducible graphics with Ruby (an example by Matt Yoder of the Illinois Natural History Survey) and using Shiny to run an R script interactively in a web interface. Matt Yoder also demonstrated the nomenclature model of Taxonworks, which is an all-in-one biodiversity/taxonomic data management system. I was particularly impressed with the elegant and user-friendly web interface. Further details about the nomenclature module in Taxonworks can be found in the abstract and slides of a talk recently given by Matt at TDWG 2017.

The third thing that really struck me is how an initially coarse idea could be quickly developed into an actual project and in some teams even transformed into a substantial product such as the Phenomap demo R package. My own team experienced the same process and we were able to generate some interesting data by the end of the workshop (see below). This was the second hands-on workshop, but the first hackathon that I attended, so it was still a relatively new experience to me and I had little to anticipate. Seeing how people with different backgrounds and who were meeting for the first time working on the same project and delivering a product within four days was simply an amazing and delightful experience for me. Gaurav, who has attended several previous hackathons (Phylotastic1, Phylotastic2, Taxonworks 2013), was impressed at how smoothly the hackathon went and how complementary many of the pitches were, with several groups providing use cases for other groups at the hackathon. The choice of participants included several centrally important people within Phenoscape and open source scientific development, such as Jim Balhoff, Wasila Dahdul and Scott Chamberlain, who formed a great on-site resource for quickly answering questions. This meant that pitches could be developed quickly, could rely on parts of the Phenoscape Knowledgebase not widely known outside its developers, and the resulting software products could build upon existing software tools, libraries and APIs.

Matching taxonomies — Guanyang’s team project

Guanyang joined the PhyloPheno team, led by Emily Jane McTavish, with Pasan Fernando (University of South Dakota) and Marjan Sadeghi (Florida State University) as co-members. Pasan, a doctoral student, works with Paula Mabee, a fish biologist and an outgoing Division Director at NSF, on a project to use Phenoscape Knowledgebase to perform ontology-enabled matrix construction and character evolution analyses. Marjan is also a PhD student and her interest is in neural networks, but also branches out to phylogenetics. Our PhyloPheno project was trying to match the Vertebrate Taxonomy Ontology (VTO) (Midford et al., 2013) with the Open Tree Taxonomy (OTT) (Rees & Cranston, 2017). The VTO is used in the Phenoscape Knowledgebase as its underlying taxonomy. It contains more than 100,000 taxonomic names compiled from multiple sources. Similarly, the OTT also draws from several sources, including NCBI Taxonomy, GBIF, and WoRMS. We will call each a synthetic taxonomy to differentiate them from their source taxonomies. It was not clear to us how the OTT and VTO synthetic taxonomies match to one another, and this question motivated our team’s project. The source taxonomies of OTT and VTO overlap, but not completely. And they were compiled at different time points and had been updated variably, the OTT a little after the VTO, which means that even the same source might appear differently in the two synthetic taxonomies. In addition, the OTT uses a priority-based method to rank different sources to deal with taxonomic conflicts (note: not to be confused with the principle of priority in nomenclature codes), which the VTO does not do. This could be another source of discrepancy.

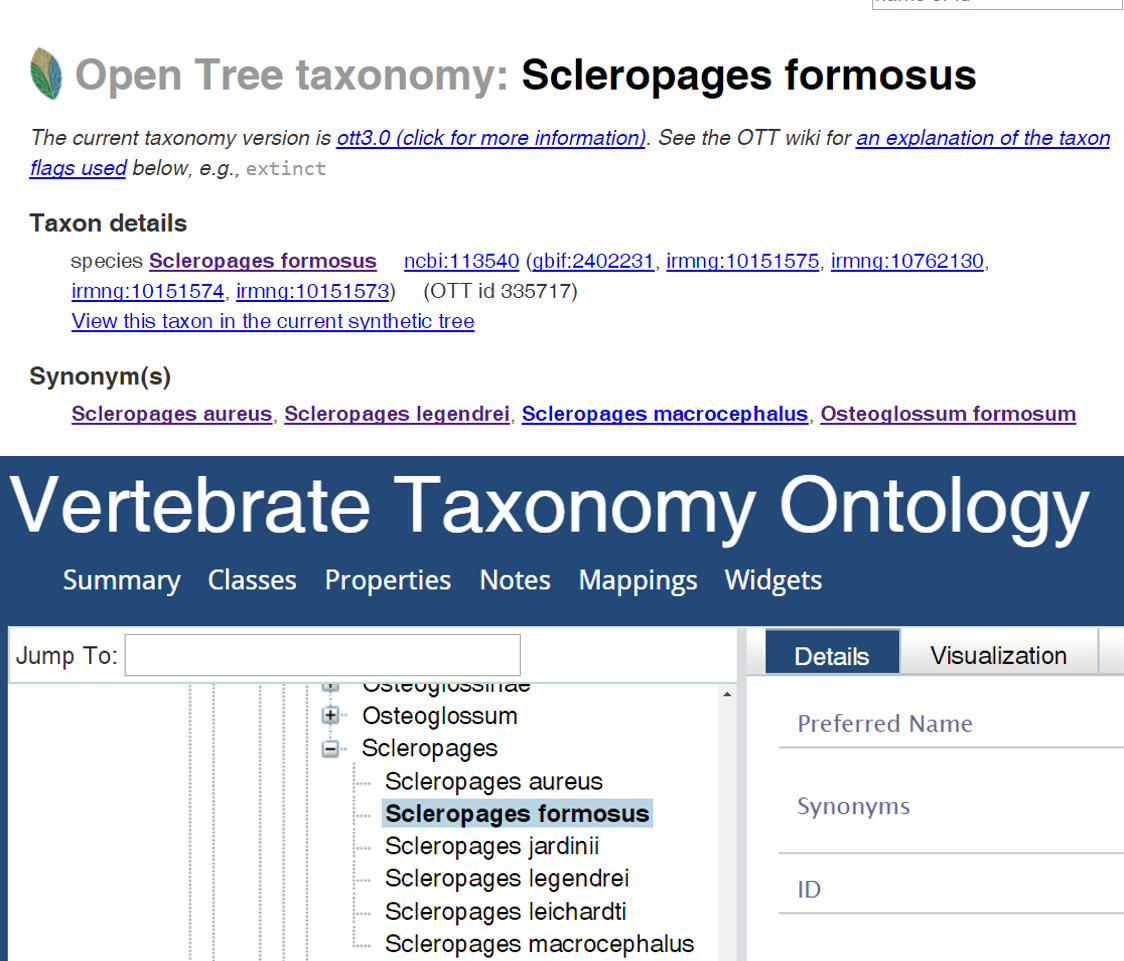

The PhyloPheno project team took a two-tiered approach to investigate the taxonomy-matching problem. We mapped names in OTT against those in VTO. The mapping could also be done in the other direction, which was not carried out during the hackathon due to time constraint. We mapped 106,884 OTT IDs (identifiers) classified as Chordata against those under the same taxon in VTO. An OTT ID refers essentially to a collection of a valid (preferred) species name and all of its synonyms. For example, Scleropages formosus is a preferred name in OTT and it has four synonyms, which are all attached to the same OTT ID 335722. We were able to match 91.5% of these IDs and the remaining 8.5% could not be matched. When I say match, I really mean three kinds of matches: (1) an OTT ID and a VTO ID are linked to the same NCBI ID, (2) the valid name of an OTT ID matches to a VTO name exactly (i.e., the two text strings are identical), and (3) a VTO name is identical to an OTT synonym. The relatively high matching rate suggests that the two synthetic taxonomies are largely consistent, and this may not be surprising as the underlying source taxonomies overlap.

We also found 1,822 OTT IDs that matched to two or more VTO IDs. For example, Scleropages formosus matched to four VTO IDs: Scleropages formosus (VTO_0033907), Scleropages aureus (VTO_0066601), Scleropages legendrei (VTO_0066599), and Scleropages macrocephalus (VTO_0066600). These three names are each considered a valid name in VTO, but are synonyms of Scleropages formosus in OTT. I looked up these names in the online “Catalogue of Fishes” (COF) and learned that the last three names are currently listed as synonyms of Scleropages formosus. This means that the OTT taxonomy is consistent with COF, but VTO is not. Trying to understand how this inconsistency arose, I did some further detective work, but could not come to a definitive answer. The synonymy was made by Kottelat & Widjanarti (2005) and should have been reflected in COF long before the VTO project. Because VTO sources its data from COF, these were supposed to appear as synonyms of Scleropages formosus. A plausible hypothesis is that because these synonyms are labeled “questionable” in COF, for some reason VTO treats these questionable synonyms as valid names, but this will need to be confirmed with the authors or developers of VTO.

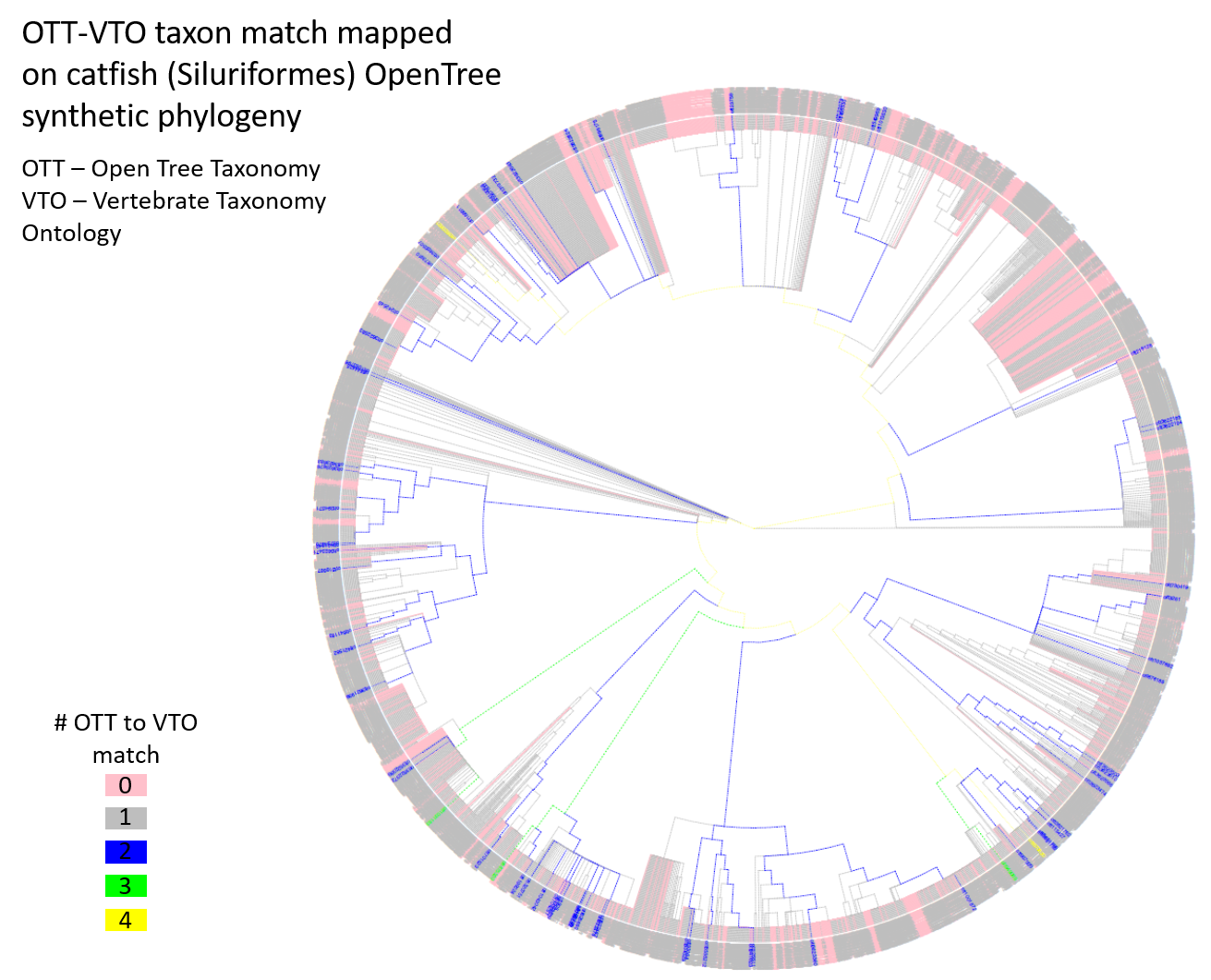

To better understand patterns of mapping between the two synthetic taxonomies, we performed another small study to focus just on catfishes (Siluriformes). There are 4,763 OTT IDs classified under Siluriformes, of which, 1,426 (29.9%) did not match to any VTO IDs, 3,265 (68.5%) matched to precisely one VTO ID, and 72 (1.6%) matched to two or more VTO IDs. At the time of the hackathon, I did not notice that the proportion (29.9%) of unmatched OTT IDs in catfishes is much greater than that (8.5%) in all Chordata. This will need to be scrutinized to make sure the analyses did not go wrong. I downloaded a synthetic catfish phylogeny from the Open Tree of Life project and visualized the distributions of OTT-VTO taxon matches on the phylogeny. This allowed us to look for clades that may show an over-abundance of unmatched or multiple-matched IDs. It appeared that unmatched IDs were rather evenly and somewhat randomly distributed on the phylogeny, with just a few clades showing a large concentration of unmatched IDs (pink branches in the figure below). OTT IDs with multiple VTO matches were also scattered on the tree. Ideally, we should investigate how exactly the mismatches (no match or multiple matches) occurred and also whether the matched taxon IDs really mean the same or congruent taxonomic concepts. We weren’t able to look into these questions due to running out of time.

The million-dollar question that quite a few other hackathon participants, and, we believe, all users of biodiversity data, have been asking is how we integrate biodiversity data when taxonomic names are used as the primary references or identifiers of the data. Comparative analyses require phylogenetic trees and organismal trait data, which nearly invariably come from heterogenous sources. Phenoscape Knowledgebase contains trait (phenotypic) data of different organisms. The Open Tree of Life project provides phylogenetic tree data (either as a synthetic tree or an original source tree). GBIF, iDigBio or other specimen-based databases contain specimen-level data (locality, collection event, repository, etc). These data are typically anchored to and accessed using taxonomic names. The Phenomap project team was trying to integrate phylogenies downloaded from the Open Tree of Life project, trait data from Phenoscape and specimen (locality) data from iDigBio, which required the reconciliation of three synthetic taxonomies. This kind of integration of heterogenous data from different sources is quite commonplace in the literature, and the main approach to reconcile taxonomies has been matching taxonomic names as text strings and synonymic relations. The problems of using names to integrate data are well-known and extensively discussed. Allowing more seamless and reliable data integration is one of the objectives of our phyloreferencing project.

NeXML to JSON-LD — Gaurav’s team project

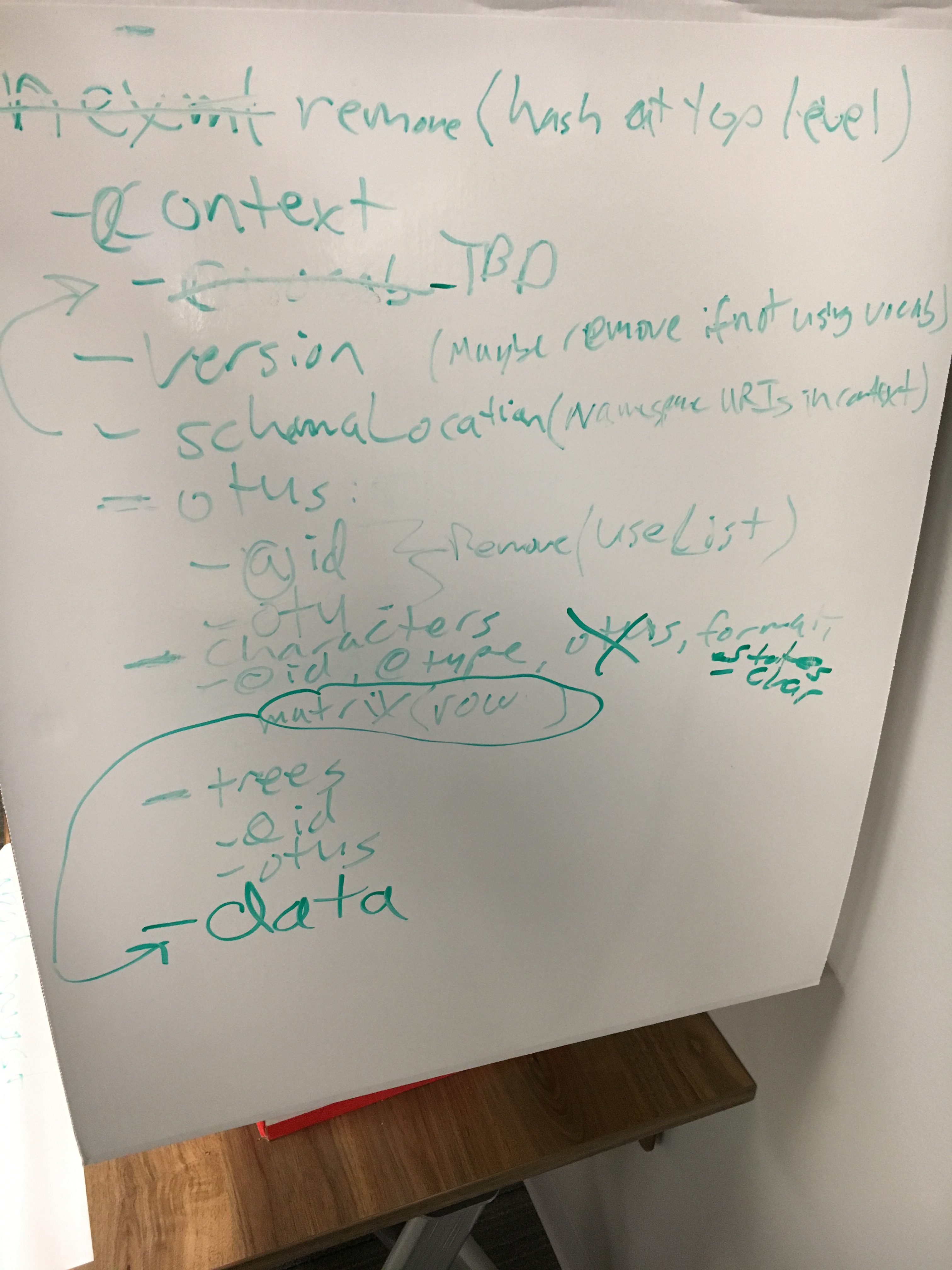

Gaurav joined the NeXML to JSON-LD group. We quickly realized that there were two competing goals within our project: Carl Boettiger and Rutger Vos (neither of whom were participants, but were following our work remotely) were interested in creating a JSON-LD representation of NeXML that would be easier to read but could be automatically converted into NeXML as required, while Mark Holder, Matt Yoder and Gaurav were more interested in developing a JSON-LD representation based on NeXML that best represented complex phylogenetic data, but that departed from NeXML when needed. We were particularly concerned about features that NeXML had inherited from the older NEXUS phylogenetics format that we felt could be represented more elegantly in JSON-LD. We wanted to ensure that our JSON-LD representation could cleanly support representations of phenotypes for taxa, such as those produced by Phenoscape’s OntoTrace tool as NeXML files. Scott Chamberlain coordinated these discussions, and although we initially created a format for a new JSON-LD represention – nicknamed “NexLD version 2” or “pheno-jsonld” (see figure) – we quickly abandoned this to focus on “NexLD version 1”, which tried to perfectly replicate NeXML as closely as possible to ensure that the formats were perfectly interconvertible.

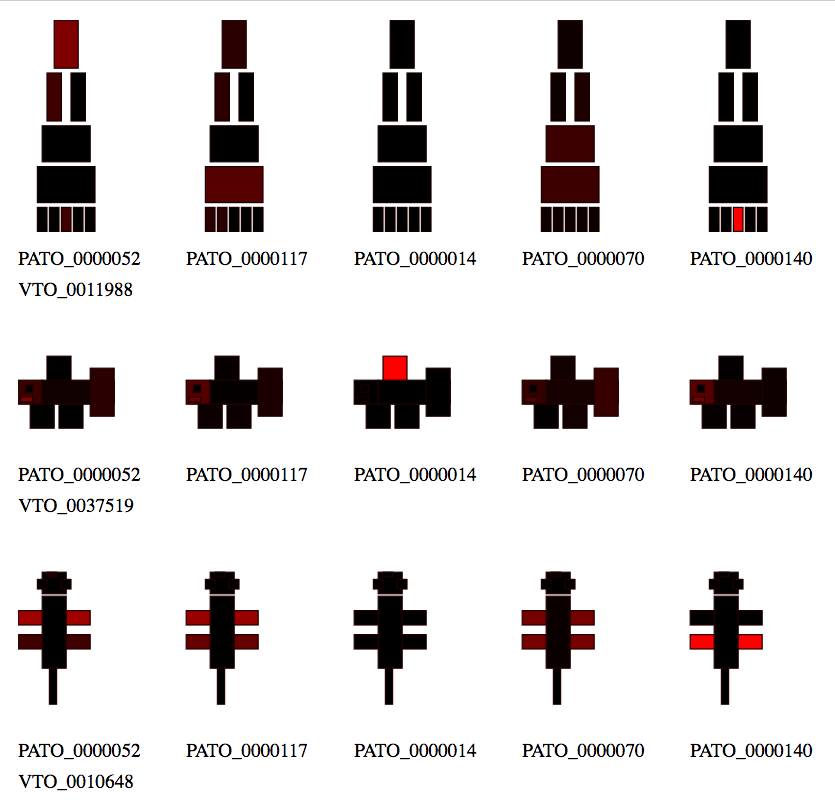

Carl had already written a R library for converting between NeXML and JSON-LD. Scott improved its support for XML namespaces, removed redundant ‘about’ keys and worked with Carl to ensure that NeXML files could be converted into JSON-LD files and back. Gaurav worked on adding additional tests to this repository, in particular making sure that it supported Phenoscape Ontotrace NeXML files. This resulted in several example JSON-LD files; a next step might be to develop the best possible frame for these objects. Mark Holder reimplemented NeXML to JSON-LD conversion in Python, while Scott tried to implement it in Ruby. Meanwhile, Scott built a low-level Ruby client for Phenoscape, which Matt used to build a visualization of Phenoscape attributes arranged anatomically. Gaurav also found a bug in DendroPy, which its developer rapidly fixed, allowing DendroPy to correctly read Phenoscape OntoTrace NeXML files.

All told, Gaurav learned a lot about how JSON-LD works and spent some time thinking about how both phylogeny and phenotypic data could be best represented in JSON-LD, a format that is frequently used in the Phyloreferencing project. He also had a chance to watch some top-notch open source developers build new software tools in a matter of days, which was both inspirational and educational in equal measure. As with all hackathons, it was also a great chance to meet and talk with interesting people working in very different areas of evolutionary biology and software development, and a welcome chance to step out of the Phyloreferencing software bubble and look at how developers have tackled challenges both very similar and very different.